We have a purpose when we try to read something. Certainly if we read a good mystery novel for enjoyment, we come to expect serial reading, because the novelist will do a slow reveal of vital clues; if you jump ahead in your reading, you may skip past a salient hint.

However, in other reading tasks, we are reading with different objectives. Maybe one's spouse has just burned herself by accident in the process of taking something out of the oven. We don't have the time to read the first aid book until it gets to the topic of burns. There are some organizers, e.g., a table of contents or an index, that facilitate accessibility in reading to do.

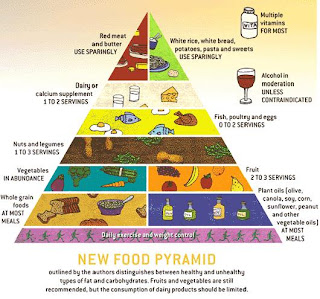

Educators often focus on a special type of organizers called advance organizers. Advance organizers facilitate learnability of relevant information. They bridge our understanding through the use of suggestive metaphors. In terms of nutrition, the USDA in 1992 introduced the food pyramid (the first embedded image below). The obvious message was ordering in numbers of suggested daily servings. I will let academic and professional nutritionists (such as the cited Willett & Stampfer) and today's Scientific American post on the pyramid-plate metaphors speak to detailed criticisms. In particular, Willett & Stampfer enhance the food pyramid in many important ways (second image).

Let me suggest some criticisms of my own and an alternate construction. For instance, the food pyramid seems to emphasize carbohydrates that in some forms (e.g., enriched flours) spike blood sugar and relevant insulin to deliver these nutrients to cells. For obese people or diabetics, these foods are counterproductive and should be used sparingly. (I do realize that specialized medical conditions may require specific diets, such as a ketogenic diet, which is often suggested for children with epilepsy. The purpose of a generalized metaphor, of course, is not to prescribe a one-size-fits-all; if someone's organs are impaired (e.g., kidney or liver), there will be dietary implications.)

I think of a cheerleader pyramid; one typically has the bigger, stronger cheerleaders at the base, with lighter, more agile cheerleaders at the top. When I conceptualize food, I think of essential nutrients--things that our bodies can't manufacture on their own. There are essential fatty acids and essential amino acids--but no such things as essential carbohydrates. If we look at essentially fatty acids, we are particularly concerned about a growing imbalance in favor of Omega-6 to Omega-3 polyunsaturated fats. We can adjust our diets with periodic inclusion of cold-water fish and/or pasture-fed animals; there are also somewhat less efficient plant-based sources, including flaxseed or walnuts. In terms of essential amino acids, meats are efficient sources of all necessary amino acids, although legumes and nuts can provide an alternative.

In the base of my pyramid, I would layer from the abstract nutritional constructs to more specific periodic (daily/weekly) dietary objectives: calories, minimum servings of monounsaturated fatty acids (e.g., extra virgin olive oil), Omega-3 fatty cold-water fish (wild-caught sardines and salmon), sufficient servings of fiber-rich foods, including soluble-fiber foods (oats, pears, berries, beans) and insoluble (e.g., whole wheat), and maximum servings of saturated fats, conventionally finished red meat, starchy, trans-fat and/or fried/breaded foods, etc.

On top of the base I might then build a basic layer of food calories subdivided in proportion to recommended daily calories (with the higher levels less preferable from a nutritional perspective); this might include an alternate presentation of the plate metaphor (below). For example, protein portions (meat/fish/poultry/dairy/beans), salad portion (leafy vegetables (e.g., spinach, romaine lettuce or kale), salad dressings (e.g., extra virgin olive oil/canola oil blends), side dishes (vegetable, whole grains), and fruit serving. We might then layer in terms of serving counts of recommended food portions. For example, we might have the key minimum number of servings at grass-fed meats (especially organ meats) and wild-caught cold-water fish at the lower level of the meat pyramid, lower-fat meats (e.g., loin meats, skinless poultry) at a second level, to sparing servings of fatty beef cuts at the top.

As to the new plate metaphor, there's a definite improvement in terms of emphasizing portion size and balanced concurrent nutrition. Marion Nestle points out that portions in the old food pyramid were misleading because a typical bagel is equal to 6 portions, a whole day's ration in itself. Nestle is critical of the plate because (I'm rephrasing) "protein" is not a food but a nutrient (i.e., so it's a convoluted mix of food and nutrients). In terms of nutrients, we have protein, carbohydrates, and fats. There are no carbs or fiber in meat, of course, although meat contains fats and proteins. You can find proteins in plant sources (beans), of course. Nestle believes that the purpose of listing the portion as protein is indirectly telling the consumer to eat less meat, because they are not specifying meat. (I'm concerned about the decreased emphasis on fats. I think low-fat diets are problematic, given the fact that we can only get certain fats from foods we eat. The emphasis on fats is, I believe, motivated by the caloric density of fats, i.e., 9 per gram.)

The reader might ask what metaphor I might suggest as an alternative advance organizer. Without going into additional detail (beyond the scope of this post), let me say I'm fleshing out the concept of a spiral staircase, with (dietary-subdivided) steps representing alternating meals and snacks (e.g., with a 3-hour interval between meals and snacks being smaller interim steps between floors--basic meals. The goal of the staircase (i.e., one's apartment/door) is the achievement of relevant behavioral/nutritional objectives. I also like the suggestive nature of stairs as representing exercise in a diet/exercise regimen.

Courtesy of the USDA |